Cook Fesperman leads talk on Black women in WWII

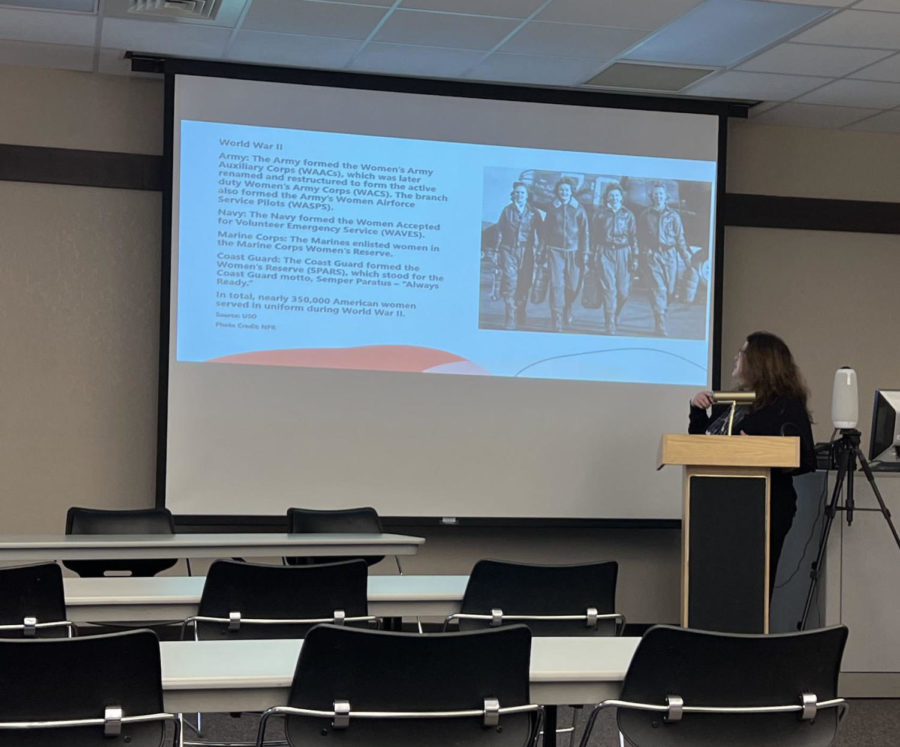

On March 23, Amanda Cook Fesperman gave a presentation about the 6888th unit of the WAAC.

April 6, 2023

In honor of Women’s History Month, Amanda Cook Fesperman, political science and history instructor at IVCC, hosted a Brown Bag Presentation titled, “The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in WWII: Special Focus on the All-Black WAAC 6888th.”

According to Cook Fesperman, the all-Black 6888th unit of the WAAC was given an impossible task in the United Kingdom.

After their motion-sickness filled voyage, during which their boat was chased by a German U-Boat, the 6888th arrived at their housing in England.

“It’s an abandoned school,” Cook Fesperman stated. “It’s not being used because of the war. It has no hot water, it has no functioning electricity… it’s leaky, it’s damp.”

Next came the difficult task assigned to the 6888th, which they were given six months to complete.

“Some people believe that they picked the Black women because they thought that they would fail,” Cook Fesperman explained.

“They were set up to deal with two years of backlogged mail sitting in six hangers in England that they had to try to sort through and figure out how to deliver.”

The unit worked day and night, dealing with rats and cockroaches, and trying to figure out whom each letter should be delivered to. Cook Fesperman mentioned some letters were addressed as vaguely as “Johnny, in England.”

“They took six hangers full of mail, they sorted it, and they delivered it correctly within three months, and people were stunned.”

The 6888th was then sent to France, where they had to repeat the process with three years’ worth of mail. Once again, they completed their assignment.

“It was really an amazing time for these women because they got the opportunity to not only prove themselves as soldiers, but to get a sense of what life was like to live in a country where you’re not constantly living in fear,” Cook Fesperman explained.

“A lot of African Americans didn’t want to come home because [in Europe] they could go places. People didn’t spit on them, and threaten to kill them, and beat them.”

According to Cook Fespermen, the women of the 6888th were not given proper recognition until 2009, when they were honored during an event at Arlington National Cemetery.

Cook Fesperman also shed light on other often unrecognized women who contributed to wars throughout all of American history.

Some of these women included Margaret Corbin and Deborah Sampson, who disguised themselves as men to fight on the front lines in the American Revolution; Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix, who were nurses during the Civil War; and Cathay Williams, the first known African American woman to enlist in the military.

An audience member in attendance also mentioned that, in World War II, women tested new planes that men felt were unsafe to fly.

To learn more about the 6888th, Cook Fespermen suggests reading Sisters in Arms, a historical fiction book about the unit, written by Kaia Alderson.