Thinking ‘I can’t?’ Try I-READ for new opportunity

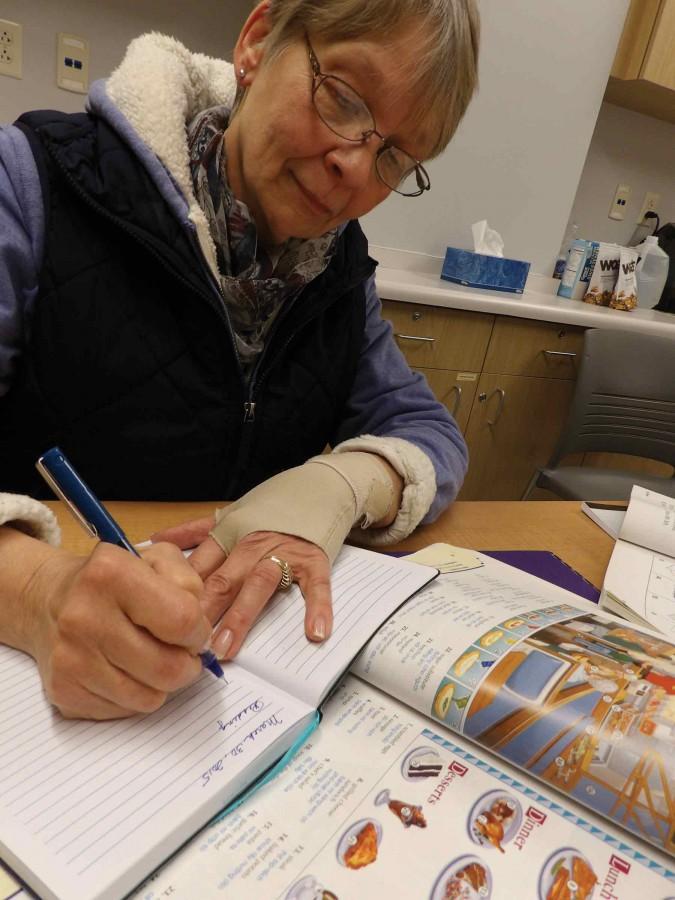

Mary Alice Steck of Hennepin works out a lesson plan for an upcoming tutoring session. Though she retired from the classroom some years ago, she turned her gift for teaching in another direction as an I-READ tutor.

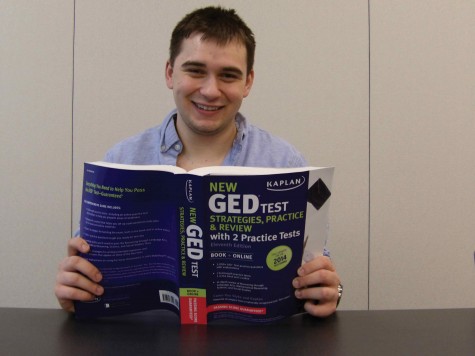

Pawel Rozycki of Peru emerged from I-READ with more than just a high school equivalency certificate. He gained confidence and a brighter future.

Behind I-READ’s plain-spoken intention lies its heart and a rich vocabulary punctuated by words like hope, promise, confidence and pride.

Along the way to improving their reading or math skills or learning English, passing the GED, keeping up with their families or getting job promotions, participants in the adult literacy program define a new life filled with something the old one didn’t have.

The volunteer tutors don’t walk away empty-handed, either.

IVCCs program turns 30 next year, and thousands of students – learners, as program manager Angela Dunlap calls them – have passed through its doors.

“A lot are frustrated with their school experience. Even though they went to school, they don’t have the skills we might expect them to have,” Dunlap said.

Education “changes how a person sees and feels about what goes on in the world,” she added, and shapes how people provide for their basic needs. When someone can’t read, or read English well, everyday activities — paying bills, communicating with doctors or children’s teachers, or getting an oil change – become a struggle. And society isn’t always forgiving or understanding.

“It can be frustrating to know that people won’t ask for help because they’re afraid of what people will do or say because they need help,” Dunlap said. “We’re not valuing people for who they are, but for what they’ve proved they’ve accomplished with a piece of paper (a certificate, a diploma or a degree).”

Because they lack a skill society determines they should have, the rest of their accomplishments and skills are undervalued and their self-confidence diminishes, Dunlap said. Helping learners recognize where they have already been successful is key to launching them toward their latest goals.

Some of the 475 learners who participate yearly get tutoring during adult basic education classes or in small groups; others in one-on-one sessions at local libraries. Funding comes through the Illinois Secretary of State’s office, which supports adult literacy and libraries.

Adult literacy isn’t child’s play. Faithful attendance can get sidetracked by family issues, job schedules or transportation interruptions, causing some to drop the program. Sometimes they come back, and sometimes they’re more determined than ever.

The program’s doors remain open “as long as you want” unless you test above 9th grade skill levels. Nearly half the learners have been working nearly two years or more.

Entrance testing “gives us a very general idea” where to start the lessons. Non-native learners are tested to see where they can improve writing, speaking and comprehending English. “Some get anxious and think they really need to do well on the test. We tell them it’s just one test and not meant to show all they know.” Interviews reveal insights into goals and past education experiences.

Tutors need not be multi-lingual to be effective. The common language of caring – plus handy translation guides and picture dictionaries — overcomes most language barriers. “It would be hard to find tutors who can speak every language our students do,” Dunlap said, listing Korea, Japan, Poland, Russia, Mexico and Bolivia as just a few of the countries. Speaking the native language may actually discourage learning English, “which is why the learner is here.”

Tutors coach, confide, cajole and convince. Several of the nearly 100 tutors have been with the program since the mid-90s. Some drop away as lives and families need attention, but rejoin. They represent all occupations and backgrounds. Some have been classroom teachers.

“Tutors love that giving-back feeling. They learn about another person, another culture.”

If not all learners can be matched with tutors, it’s usually a matter of geography. “I have 11 people waiting for tutors – but I also have tutors waiting to tutor. If a tutor lives in Ottawa and the learner is in Princeton, it’s not going to work.”

Chemistry is unpredictable, she added. Sometimes, both sides emerge from the shared effort the best of friends whose relationship continues after the lessons end.

Dunlap becomes a referee of expectations, and cautions learners and tutors not to be disappointed if there aren’t Hallmark moments. Some successes come in glimmers rather than bursts of fireworks, as when one learner approached a math problem for the first time without bursting into tears. Getting what they want from the program, Dunlap reminds, rests with the learners.

With hardly a pause, Dunlap conjures up success stories. One learner’s diligent study was rewarded by attaining a high school equivalency in a year – an astounding rate for someone who arrived in the program with fourth-grade reading skills and a ton of emotional baggage.

“I wanted to prove I wasn’t stupid and could do what I’d been told I couldn’t,” the learner, who later enrolled in a university, told Dunlap.

“Really,” Dunlap adds, “this is a lot about intangibles. There isn’t a test to measure confidence. What we do isn’t like going to a tree and picking off an apple. There is no tree. We don’t know what we do that gets results. But when we change a life we change it — and I’m totally gratified to be here.”