‘Totally gnarly’: ’80s music returns

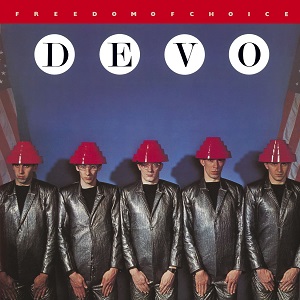

Devo produced the album “Freedom of Choice” during their heyday. Photo available from Wikimedia.com under Fair Use.

September 1, 2022

This summer, something happened that for us GenXers was totally gnarly. Kate Bush, an artpop musician whose heyday ended, like, over 25 years ago and who received relatively little airplay in the U.S. suddenly had her 1985 song “Running Up That Hill (A Deal with God)” go mondo huge. Then Metallica’s 1986 “Master of Puppets” started gaining in popularity as well. Unless you’ve been living under, like, a rock or something, I’m sure you’re aware that this is due to their prominent roles in the storyline of the latest season of “Stranger Things. “

For those like myself who grew up in the ’80s, the show has been a veritable smorgasbord of nostalgia: D&D (and the “Satanic panic” surrounding it), roller rinks, skateboarding, classic toys like Star Wars and Masters of the Universe, ugly but rugged bicycles, ugly but rugged cars (in season 4 I even saw the light blue 1975 Ford Maverick my mother owned when I was a child), wood paneling, pervasive chain smoking, video arcades, talking with friends by walkie-talkie, Valspeak and other 80s slang, true-to-the-era hairstyles and fashion (as opposed to the typical exaggerated presentation the 80s gets); and this season, characters whose appearances are clearly modeled on Allison Reynolds from The Breakfast Club (Eden Bingham), Samantha Baker from Sixteen Candles (Vickie), and guitar god Eddie Van Halen (Eddie Munson). (And I will eat my hat if Erica Sinclair isn’t based on Dee Thomas from What’s Happening!!.)

For those like myself who grew up in the 80s, the show has been a veritable smorgasbord of nostalgia: D&D (and the “Satanic panic” surrounding it), roller rinks, skateboarding, classic toys like Star Wars and Masters of the Universe, ugly but rugged bicycles, ugly but rugged cars (in season 4 I even saw the light blue 1975 Ford Maverick my mother owned when I was a child), wood paneling, pervasive chain smoking, video arcades, talking with friends by walkie-talkie, Valspeak and other 80s slang, true-to-the-era hairstyles and fashion (as opposed to the typical exaggerated presentation the 80s gets); and this season, characters whose appearances are clearly modeled on Allison Reynolds from The Breakfast Club (Eden Bingham), Samantha Baker from Sixteen Candles (Vickie), and guitar god Eddie Van Halen (Eddie Munson). (And I will eat my hat if Erica Sinclair isn’t based on Dee Thomas from What’s Happening!!.)

And of course, there’s the choice tunage. From the beginning the show has used period music quite liberally, and often in ways that significantly enhanced the narrative—think of the uses of Peter Gabriel’s somber cover of David Bowie’s “‘Heroes’”, Foreigner’s “Cold as Ice”, and the comically frequent use of Musical Youth’s “Pass the Dutchie” when loveable stoner Argyle is on screen.

As a result, it’s brought some of the music of my youth to the attention of today’s youth. So if you’re jonesing for more, peg up your jeans, flip up that collar, put on those shades, and let me take you on a Journey (whose 1983 “Separate Ways (Worlds Apart)” both opens and closes the first part of season 4) to visit some other bands from that time that are not just the bomb, but that genuinely have something to offer you in the here in now. Come on; it’ll be very.

Here are 10 ’80s bands that you should be listening to right now.

#10: New Order (1980-present).

New Order is cooler than anything you’re listening to; I can almost guarantee it. There’s just something about electronic music that makes it reek of awesomeness, and New Order has perfected the genre. Rising from the ashes of Joy Division after the suicide of original lead singer/songwriter Ian Curtis, New Order moved in a less brooding, and more electronic direction. Bernard Sumner’s guitar playing is butter, and combined with Gillian Gilbert’s bodacious keyboard and synth chops, and lyrics that stimulate your grey matter, you have an electronic symphony so cool you’ll need to wear a parka to listen to it. “True Faith” and “Blue Monday” (part of which some of you may have heard on a recent Call of Duty commercial) groove like few songs before or since. Your body can’t help but respond to their multiple driving beats. “True Faith” is easily the coolest sounding song of the decade. Throw in songs like “Let’s Go (Nothing for Me)”, “Age of Consent”, “Round and Round”, and the classic “Bizarre Love Triangle” and you will be one happy camper listening to this. Unlike the disco era that preceded electronic dance music, this is music for your whole self, not just your feet and hips. Just be sure the ‘rents aren’t around when you play it because they might start dancing in front of you and your friends, which would be a total barf-o-rama.

#9: R.E.M. (1980-2011).

R.E.M. has had a long and very successful career, but they would make it on this list even just from their 1987 album Document. Document is a mirror held up to American society, though its aim is ultimately to serve as a site of resistance—as Marx once said, ”the point, however, is to change it.” “Finest Worksong” examines how capitalism creates bogus needs to keep us in thrall to work. “Welcome to the Occupation” and “Exhuming McCarthy” lay bare the pervasive forces of counter-resistance from The Man that tries desperately to maintain the status quo; a counter-resistance that, as “Disturbance at the Heron House” reminds us, can be overcome only through a bum-rush by those forces the status quo considers “chaos.”

Document deftly reveals how everything has been degraded—work, culture, love (where, as “The One I Love” reminds us, those we love often become “a simple prop to occupy my time”), and even armageddon (“It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)”). 1989’s “Pop Song 89” and 1991’s ”Shiny Happy People” do a great job of continuing this while showing off the band’s satirical side. So pop Document into your Walkman and prepare to have your mind blown.

#8: Siouxsie and the Banshees (1976-1996).

Did you listen to that wicked song played with the end credits of the last episode of season 4? If you did, what you heard was one of SatB’s greatest compositions, 1981’s majestic “Spellbound”. One of the pioneers of both Goth style and music, a Goth subculture reader’s poll once ranked them the #2 Goth band of all time, behind only The Cure, and with #3 not even being close. With unconventional inspirations like history, horror novels, urban legends, and film noir, SatB’s music is both sinister and beautiful, almost hypnotic at times. Like the Decadence movement in literature, songs like “Playground Twist”, “Carousel”, “Cities in Dust” “Candyman”, “Happy House” and “Scarecrow” create beauty out of the abject, the tragic, and the grotesque.

And Siouxsie Sioux’s voice is an instrument unto itself; perfectly fitting the mood of the music—alternately anxiety-inducing and strangely soothing. Her tight use of crescendo and decrescendo in “Rhapsody” surpasses anything you’ll hear outside of classical music. Bertolt Brecht once promised us that there would be singing about the dark times. Siouxsie and the Banshees delivers on that promise with an oeuvre whose music envelops its listeners and whose lyrics inspire flights of imagination.

#7: Tears For Fears (1981-present).

After the last several years, I’m sure many of us need something to lift us up, to make us feel right (or at least okay) with the world again. While one of the hallmarks of 80s music was its often feel-good and party-hearty themes, the band that can do this better than any of the others at the time is Tears For Fears. I’m not sure whether it’s the smooth flow of the music, or Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal’s powerful crooning voices, but listening to TFF is soothing; it’s a musical chill pill for the soul. But unlike the steady stream of “light FM” and “slow jams”, this isn’t just ear or brain candy.

TFF accomplishes this without mindless naivete, or by ignoring or minimizing the trauma the world puts us through. Instead, inspired by their early interest in primal scream therapy, they tackle it straight on. (I mean, they’re not, like, The Gufs or something. Ew.) Thoreau once said that “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” TFF’s first charting single, “Mad World,“ expressed that desperation as well as anything I’ve ever heard or read. The opening lines of one of their biggest hits, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World,” are a slap in the face with cold, hard reality: “Welcome to your life/There’s no turning back.”

Their output from 82-85 (which includes some truly stellar songs like “Head Over Heels,, “Mothers Talk,” “Pale Shelter,, “Shout,“ and “Suffer the Children”) is nothing short of a New Wave spiritual experience the will put your soul at ease without lobotomizing your brain.

#6: Pet Shop Boys (1981-present).

According to music lore, July 12, 1979, was the day that disco died. But just as a caterpillar becomes transformed into a butterfly, disco lived on after a metamorphosis. What it became was Pet Shop Boys, who combined disco’s distinctive beat and rhythms with electropop (before it even had the name), and more than a dash of showtune and classical music thrown in for good measure. (In “Left to My Own Devices” singer/songwriter Neil Tennant mentions how as a child, he imagined “Che Guevara and Debussy to a disco beat”.)

Unless you already listen to Pet Shop Boys, they’re like nothing you’ve heard before. Their unique style (which includes an easily recognizable combo of dramatic music with nearly deadpan singing) would already make me want to recommend them, but the primary reason they’re here is because their beautifully poetic lyrics center around something many of us could really use right now: ironic detachment. Their songs explore all aspects of life, from the normal themes of rock music like love (“Heart) and betrayal (“What Have I Done to Deserve This? and “Can You Forgive Her?”) to more unconventional themes like living in the closet (“In Denial”) or suburban decay (“Suburbia”), and even the mundane elements of daily life (“Shopping” or “I Want a Dog”).

All the while Pet Shop Boys treats them with an irony that reveals their strangeness, and often their emptiness. “Heart”, for example, generally sounds like a typical love song, save for the blatantly honest lyric “If I didn’t love you/I would look around for someone else.” “Rent” admits that the singer loves his beloved because they spoil him, in return for which he’s content being their “puppet.”

The neoliberal capitalism of Thatcher and Reagan, with their emphasis on creating opportunities (especially to be unemployed due to downsizing) gets reduced to its absurd essence in “Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots of Money)”: “I’ve got the brains/You’ve got the looks/Let’s make lots of money.”

Tennant’s religious school upbringing is exposed for its basic inhumanity and guilt-tripping in “It’s a Sin” where literally “everything I’ve ever done, everything I’ll ever do” is a sin. At a time when the COVID pandemic has challenged and changed how we engage with the world and each other, Pet Shop Boys can give us a refreshing new mind frame on what we previously considered ‘normal’.

#5: Gary Numan (as Tubeway Army, 1977-1979; as Gary Numan 1979-present).

Gary Numan is the ultimate paradoxical musician. Paradox #1: while the music for which he’s best known was released 40 years ago, there’s little doubt that Numan’s sound still belongs to the future (for a great example, see the opening synth riffs from “Me! I Disconnect from You”). Listen to Tubeway Army’s 1979 album Replicas, and Gary Numan’s albums The Pleasure Principle (1979) and Telekon (1980). These albums are electronic wunderkinds that sound like they came from the 25th century. Someday, most of you will have grandchildren, and the music they listen to might well sound like Gary Numan.

Paradox #2: Numan’s lyrics mechanize the human and humanize the machine, blurring the lines between them. Numan’s (i.e. New Man’s) songs are populated with humans and machines in fairly equal measure, exploring the possible relationships between them, from robot prostitutes (“Are ‘Friends’ Electric?” and “Down in the Park”), machine/human hybrids (“The Machman”), machines that have fallen in love with their creator (“Engineers”), people that rely on their machines for comfort (“Cars”), and a lonely machine regretting the extermination of humanity (“M.E.”).

Paradox #3: Numan is himself both human and alien. One way in which Numan is still relevant, and perhaps even more relevant today, is the way in which he performatively challenged any sense of stable and dichotomous identity. His androgynous appearance and stiff, quirky mannerisms from that time period were described by reviewers as “alien” and “android,” an impression he continued to make for years.

Numan’s entire oeuvre from the late ’70s and early ’80s, in sound, subject, and even appearance, challenges the maintenance of simplistic dichotomies. Gary Numan is still the future. Of course, maybe you’re not ready for him yet, but your grandkids are going to love him.

#4: The Smiths (1982-1987).

Let’s face it, right now a lot of things are totally bogus. School, jobs, relationships, politics… everything blows chunks. So who do you listen to when everything sucks? You listen to The Smiths. The Smiths get it like no one else does. Both the lyrics and singing of Morrissey just ooze disillusionment; one of their earliest hits, after all, was “What Difference Does It Make?”

Will your career make you happy? According to “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now”, no. Will you find satisfaction by attaining some sort of significant accomplishment or recognition? Sorry, but “You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet, Baby.“ The abusiveness of early education is on full display in “The Headmaster Ritual,” and family, as “Barbarism Begins at Home” explains, is no better. What about love? Don’t count on even finding it, “How Soon is Now?” reminds us—“you go and you stand on your own/and you leave on your own/and you go home and you cry/and you want to die. And even if you do manage to find someone, maybe something bad will happen and you’ll end up with a “Girlfriend in a Coma” or both get killed by a double-decker bus (“There is a Light that Never Goes Out”).

The world painted by The Smiths is raw, abusive, frustrating, disappointing, and unbearably and starkly real. This is heavy music. One would think that this would induce despair; but if the testimony of their fans says anything, it’s that instead their music has spoken to people in their suffering, and provided a feeling of camaraderie with the band members that had led to their music being called “songs that saved your life.”

Let’s face it, after the last few years—the rise in intense public displays of bigotry, the angry polarized social media arguments, the social and political unrest, the continuing pervasiveness of war, the recent crippling inflation, the effects of the COVID pandemic—everyone could use someone who understands just how craptastic everything really is, and doesn’t patronize you with naïve and empty reassurances. The Smiths is that friend.

#3: Fishbone (1979-present).

With a style influenced by punk, funk, hard rock and ska, no one cranks like Fishbone. They certainly have a unique sound that’s still funky-fresh more than 40 years later, but the reason I placed them so high here is because of the content of their music. Many Fishbone songs are the 60s protest music of the 80s.

Outside of gansta rap artists like Public Enemy and N.W.A., nobody so effectively expresses the experience of urban blight and the resistance to the conditions that created it as Fishbone. They first entered the public arena with their anti-nuclear war song “Party at Ground Zero” and “Ugly” their critique of President Reagan (which they re-dedicated to President Trump a few years back). Through at least the mid-90s, their work expressed both the despair that arises from the abandonment of poor urban populations (in such songs as “Sunless Saturday”, “Ghetto Soundwave”, “Subliminal Fascism”, and their cover of Curtis Mayfield’s “Freddie’s Dead”) or the increasingly long delay of racial justice (in “Slow Bus Movin’ (Howard Beach Party)” and “One Day”), but without ever abandoning hope for creating a better world (on display in one of the most beautiful songs of the decade, “Change”, or more recently in their promise of a coming “Karma Tsunami”).

They broke from the naïve hopefulness of much of the decade’s music to address its dark underbelly; but in a way that inspires resistance rather than resignation. The problems that inspired these songs (such as broken families, poverty, drugs, hopelessness, uncaring politicians, racism) are still with us, and in some places progress on them has even backslid; and hence their work still carries messages relevant for today.

#2: Dead Kennedys (1978-1986).

It’s no secret that many people have been expressing intense frustration with both Republican and Democratic politicians, often even declaring them to be different sides of the same coin. Growing out of San Francisco and California politics of the late ‘70s, perhaps no band has reflected that attitude of universal rejection better than Dead Kennedys.

DK is a middle finger to the whole system, a universal dis; their targets include conservatives (exemplified in songs like “Kill the Poor” and their critiques of Reagan: “Rambozo the Clown” and “We’ve Got a Bigger Problem Now”), liberals that act just like conservatives (such as then S.F. Mayor Diane Feinstein, infamous for the police brutality—physical and sexual, mistreatment of the poor, and gentrification under her administration: her policies are targeted in songs like “Police Truck” and “Let’s Lynch the Landlord”), wishy-washy do-nothing hippies (exemplified by DK’s most well-known song, “California Uber Alles” which satirizes Governor Jerry Brown’s “new age” nonsense and lack of any coherent platform), careerist yuppies (targeted in “Holiday in Cambodia” and “Night of the Living Rednecks”), defenders of toxic masculinity (“Macho Insecurity”), organized religion (one of their albums is titled In God We Trust, Inc., and includes songs like “Religious Vomit” and “Moral Majority”), and even the music industry itself (“Pull My Strings” and “Chickens— Conformist”).

DK music is angry; it’s fed up. It says “we know this is all crapola and we’re not going to pretend it isn’t”. While many of their songs are clearly grounded in historical circumstances (Brown and Feinstein are no longer in those offices, and Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge are no longer in charge of Cambodia), they still include themes and concerns that are currently relevant (police brutality hasn’t gone away, and there’s still middle-class white youth that tries to aggrandize themselves through completely superficial associations with POC and the poor); and perhaps no band of that era can so easily resonate with the growing fed-up-ness with the current political climate as DK.

And #1: Devo (1973-1991, 1996-present).

“The ‘Whip It’ guys? No way!” Way! “Whip It” may be the song that everyone knows (which, along with their dressing in such things as plastic hairdos, hazmat suits, and energy hats, probably leads many people to think of them as something like a “novelty” group); but Devo is so much more than just whipping it good.

Devo, three of whose founding members were students at Kent State University and were present at the time of the 1971 Kent State shootings (where the Ohio National Guard fired on student anti-war protestors, killing four), is built off of the idea that the world is devolving, deteriorating; and not just with our apathetic acquiescence, but with our active and gleeful participation. (‘Devo’ is short for ‘de-evolution’, after all.) It is the self-described “first postmodern band.”

Devo’s musical theater (and it is theater—they were doing multimedia concerts and music videos before pretty much anybody) is a rapid-fire condemnation of contemporary society: its mindless conformism (“Freedom of Choice”), its papering over horror and atrocity with naïve optimism (“Beautiful World”), its crass commercialism (“Devo Corporate Anthem” and “Too Much Paranoias”), its crude hyper-masculinity (“Triumph of the Will”), its reduction of life to meaningless toil (“Working in a Coal Mine” and “Clockout”), and its reduction of human beings to mere cogs in some great, glitchy machine (their pseudo-cover of “Secret Agent Man”).

Devo takes these elements of society, all still present or even magnified today, and ruthlessly exaggerates them in a way that puts their absurdity on full display. They are the pioneers of rock satire. They are the prophets of anxiety (on full display in their nerve-wracking cover of “Satisfaction”) sharing with us a gospel of disillusionment and decay. They are our musical canary in the coalmine, desperately trying to warn us of the existential danger we’re all in.

As such, perhaps no ’80s band is more needed in our present moment.

Jason Beyer • Sep 6, 2022 at 6:47 pm

Some honorable mentions:

The Cars (1976-88, 2010-11); for the meta nostalgia they provide by themselves being a new wave appropriation of classic rock and roll. (Their song “Moving in Stereo” was used in some pool scenes with Billy in Stranger Things, though it’s best know for its use in the oft-mentioned film Fast Times at Ridgemont High.)

Crass (1977-1984); for being the punk band that took the punk ethic the most seriously with results similar to Dead Kennedys but more focused on England. How can you not love a band whose members have names like Steve Ignorant, Joy de Vivre, Eve Libertine, Penny Rimbaud, G. Sus and N. A. Palmer?

Gang of Four (1976-84, intermittent in the 90s, 2004-2020); another strong punk/rock band that placed more emphasis on critique of the status quo than more well known bands of that sort like The Clash.

Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five (1978-83, 1987-88); for being the pioneers of many standard elements of rap and hip hop: the use of turntables and sampling, beatboxing, crossing the performer/DJ line, and socially conscious lyrics.

Public Enemy (1985-present); for reasons similar to what I gave for Fishbone but with a definite gangsta rap style and more than a hint of the 1960s Black Power movements. “Fight the Power” is still an anti-establishment classic.